By Robin B. Williams, Ph.D.

Which is the more appropriate symbol of Savannah: a horse-drawn carriage or a Gulfstream jet?

The quick answer would be to choose the former. The city’s built environment, with its many historic buildings, squares, cobbled streets and horse-drawn carriages, attracts millions of tourists each year eager to experience a bygone era. But does the city’s palpable antiquity prompt visitors and perhaps locals as well to see Savannah as being locked in the past and behind the times? For decades, the city’s image (often promoted by the Chamber of Commerce, but also by the City of Savannah itself) has looked to its colonial past for a municipal identity, with a tricorn hat atop the capital S in Savannah long serving as a municipal logo. More recently, advertisements represented Savannah with the simple phrase “Est. 1733” refer to the year of Savannah’s founding.

But is a horse-drawn carriage an accurate symbol of Savannah and its past? Might a Gulfstream jet, manufactured in Savannah, be a more appropriate representation of the city and its long history of embracing innovation?

Enlightenment Idealism and the Creation of an Innovative Urban Environment

Throughout Savannah’s history, municipal officials, local planners and architects, companies and individuals, have embraced progressive and innovative ideas, sometimes with the city being at the national forefront of development.

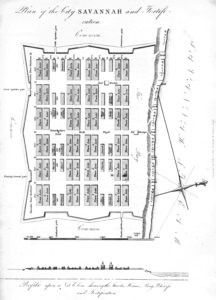

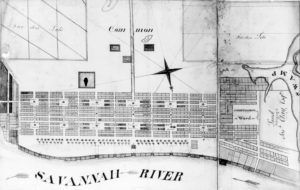

The goal of equality was built into the urban plan of Savannah, with its use of multiple urban squares, each forming the center of a neighborhood unit, or ward, and flanked by four public building “Trust” lots.The repetitive nature of the ward plan ensured a multi-centered town, with a distribution of power that differed greatly from the usual concentration of power around a single square in other cities.

Oglethorpe’s openness to minorities guided him to welcome Jews to the fledgling Georgia colony at a time when they were unwelcome in most places. He also embraced Tomochichi, the chief of the local Yamacraw Native American tribe, as a fellow head of state, presenting him to the British parliament, the King and Queen and the Arch-Bishop of Canterbury. Upon Tomochichi’s death in 1739, he was accorded a state funeral and was buried in the center of Percival Square (now Wright Square), over which a monument, perhaps the first public monument in America, was erected. Such remarkable and respectful treatment of a Native American had no equal prior to the 20th century.

Savannah’s Progressive Embrace of Trees

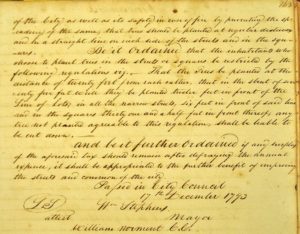

The urban plan itself famously included a square at the center of each ward and astonishingly wide streets for the early 18th century, which provided ample space for trees. It remains unclear at what point trees were first actively planted in the city, but certainly by 1793, shortly after the city had incorporated, the city council passed ordinances protecting trees and regulating the location and pattern of their planting.

Among the reasons for promoting trees were environmental concerns, since trees provided much-desired shade in the hot climate and they believed the trees helped absorb the “miasmas” that came from the marshes around the city.The formal rows of trees planted in the Strand along the north side of Bay Street was likely only the second such allée of trees in the country (after one planted in the Boston Common).This was at a time when trees in bigger cities, like Philadelphia and New York, were attempting to ban street trees.

Trees became such an important part of Savannah’s urban identity, that the city was known as “Forest City” during the 19th century. Beyond the squares and tree-lined boulevards, Forsyth Park was one of the earliest municipal parks in the country, established in 1851. The 1896 establishment of the Park and Tree department within the municipal government, an early example of such a department, assured the city’s commitment to trees would continue into the next century. In 1984, the Candler Oak became the first individual tree in the nation to receive a protective conservation easement.

Innovative Charitable Institutions to Care for the Needy

Socially, the city witnessed some of the nation’s earliest efforts to improve the lives of the sick and needy. The Bethesda Home for Boys, established in 1740, was among the first charitable organizations in America. The 1804 establishment of a seaman’s hospital, one of the oldest hospitals in the country and first in Georgia, led to the creation of the Savannah Poor House and Hospital in 1808. Its building from 1818 still stands; its alteration in 1877 accommodated what may have been the first “Nightingale Wards” in the country.

Chartered in 1832, the Georgia Infirmary, the oldest known black hospital founded by whites in the United States, included the nation’s first nursing school for African American students, operating from 1904 to 1937.

A strong tradition of female philanthropy was led by Mary Telfair, who bequeathed her wealth in 1883 to create the Telfair Academy of Art and Sciences, the first public art museum in the South, and the Telfair Hospital for Females a year later, the first of its kind in Georgia. Such actions inspired another wealthy Savannah woman, Juliette Gordon Low, to establish the Girl Scouts of the United States of America in Savannah in 1912.

Savannah’s Openness to New Architectural Technology

Architecturally, Savannahians welcomed new building technology on multiple occasions. Wealthy banker and shipping merchant Richard Richardson hired English architect William Jay, among the first professionally trained architects to practice in the United States, to design his mansion overlooking Oglethorpe Square. Now known as the Owens-Thomas House, it showcased cutting-edge English technology with its one-story structural cast iron side porch and gravity-fed indoor plumbing, including showers and flush toilets, with water supplied by interior cisterns storing rain water – both among their earliest uses in the country.

The U.S. Custom House on Bay Street, designed in 1848 by New York architect John Norris and completed in 1852, was among the first buildings in the country to boast internal cast iron and wrought iron interior structural supports and possesses the oldest extant self-supporting wrought iron roof with its massive metal pleated plates.

Early skyscraper technology of steel framing, curtain walls and the elevator, a combination first used in Chicago in the 1880s, arrived in Savannah in 1895 with the Citizens Bank of Savannah (now SCAD’s Propes Hall). A decade later, the new City Hall embodied the spirit of modernity with its Beaux-Arts classical style inspired by the celebrated 1893 Chicago World’s Fair and its bold interior use of electric lights and a prominent open-cage elevator around which the stairs dramatically rise. The Drayton Arms Apartments (now Drayton Tower), erected in 1949-51, was among the nation’s early expressions of the highly modernistic International Style and brought a new standard of modern living to the state as the first air conditioned apartment building in Georgia.

Innovation on the Rails and Roads of Savannah

Despite its relatively small size, Savannah played an important role in national developments of transportation technology. In the early 1850s, at a time when railroads were in their infancy, the Central of Georgia Railroad embarked on an innovative complex that integrated passenger, freight, and repair service as well as design and corporate offices in a single 33-acre site. That it survives as one of the most complete historic railroad facilities in the world only adds to its significance.

Municipal leaders in late 19th-century Savannah understood the importance of paved streets to the modernization of the city, leading to experimentation with a wider array of paving materials than in most other cities. In the early 1900s, Savannahians embraced automobile technology with gusto. In 1904 T.A. Bryson erected a Packard Motor Car Showroom and Automobile Garage facing Chippewa Square, a remarkably early example of this new building type. Now called Bryson Hall, it retains its original Art Nouveau style copper inscription atop the façade.

Savannah’s mild winter climate, flat topography, sandy soil and enthusiastic autoists, as they were called at the time, helped secure the city as the site of the nation’s first stock car race in March 1908 and first Grand Prix race in November that same year. Thus began the so-called Great Savannah Races, which also took place in 1910 and 1911 and attracted automobile manufacturers from around the world to test their cars on the longest race track in the country. The permanent legacy of those races would be early examples of automobile suburbs planned in 1910 – Ardsley Park and Chatham Crescent.

A Legacy of Innovation

The desire of many locals and visitors to preserve as much of Savannah’s glorious architectural heritage as possible in the years after World War II, at a time when most cities gleefully sacrificed their past for the shiny promise of new development, was its own form of innovation. But the rise of historic preservation and the heritage tourism it encouraged fostered a popular perception of Savannah as an old place, where the past lives on and change, at least in the older parts of the city, represents a threat.

As a member of the Historic District Board of Review for over six years, I witnessed this tension between preservation and change on a monthly basis. A city that aims to preserve the past at all costs runs the risk of turning a living historic city into a museum. As an architectural and urban historian who has lived in cities new and old (Toronto, Philadelphia, Rome and Savannah), I have seen ample evidence that the healthiest cities find a balance and don’t shy away from innovation.

It is in Savannah’s urban DNA to be innovative, but are we currently living up to that legacy?

Robin B. Williams, Ph.D., chairs the Architectural History department at the Savannah College of Art and Design, where he has taught since 1993. From 1997-2006 he directed the Virtual Historic Savannah Project, still available online at vsav.scad.edu. He is the lead author of Buildings of Savannah, a new comprehensive guide to the city’s architecture, landscape and urban planning published by the University of Virginia Press (2016). He has also published on the history of commemorating Tomochichi in Savannah and the history of Savannah’s street pavement, which has led to his current research and documentation project showcased online at www.historicpavement.com. He can be contacted at rwilliam@scad.edu.