My name is Ana Beasley, and I am a graduate student at Georgia Southern University, working on my master’s degree in history. My focus in public history is in K-12 educational programming for museums and archives. Children that engage in historical thinking processes can learn valuable skills pertinent to their education and future. These skills transcend history education. Historical thinking helps students to analyze and interpret a variety of information whether it is labelled “history” or not.

In August 2019, I began my internship with the Georgia Historical Society (GHS) working on my thesis project. I worked with the GHS education department creating educational resources for the Georgia History Festival (GHF). Each year during the Festival, GHS selects a person or topic that made a great impact on Georgia’s history as the focus of educational programs and resources. The 2020 focus of study is “Women’s Suffrage at 100: The 19th Amendment and Georgia History.” New educational resources explore the legacy of women’s suffrage in Georgia and the United States.

As part of GHF, GHS invites educators and students in grades K-12 to participate in the Georgia Day Parade. As part of the annual commemoration of the founding of the Georgia colony, students, local dignitaries, musicians, and costumed performers march through Savannah’s historic squares. Elementary and middle school students marching in the parade are invited to participate in the Banner Competition. Students design banners based on the annual theme and march behind their banners during the parade. The theme of this year’s Georgia Day Parade Banner Competition is “Finding My Voice.” The new classroom resources that I developed engage students in exploring the process of developing points of view, exercising civic rights, and responding to changes in society based on the lessons learned from the women’s suffrage movement.

To assist teachers in teaching this theme, I chose primary sources from the GHS collections as well as the Library of Congress and paired them with appropriate teaching strategies for classroom instruction. For example, suffragists used non-violent protests in the early 20th century, similar to those associated with the Civil Rights Movement seen later in the 20th century.

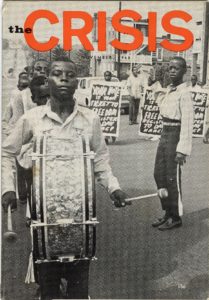

In one activity, students compare a 1916 photograph showing women marching in protest of the re-election of President Woodrow Wilson in Chicago with a cover of The Crisis Magazine from the NAACP that shows teenagers marching for voting rights in 1968. This activity gives students an opportunity to investigate the use of non-violent protest to gain voting rights over time.

It has been my privilege to visit an array of classrooms in the Savannah area to teach and share these resources. Students work together to solve historical inquiries and participate in active discussions about primary sources—they are engaged, curious, and involved. They practice analyzing and interpreting historical artifacts and are challenged to think like historians. Through this project and the support of GHS, I have gained a better understanding and appreciation for the far-reaching effects the practice of historical thinking can have on a child’s education.