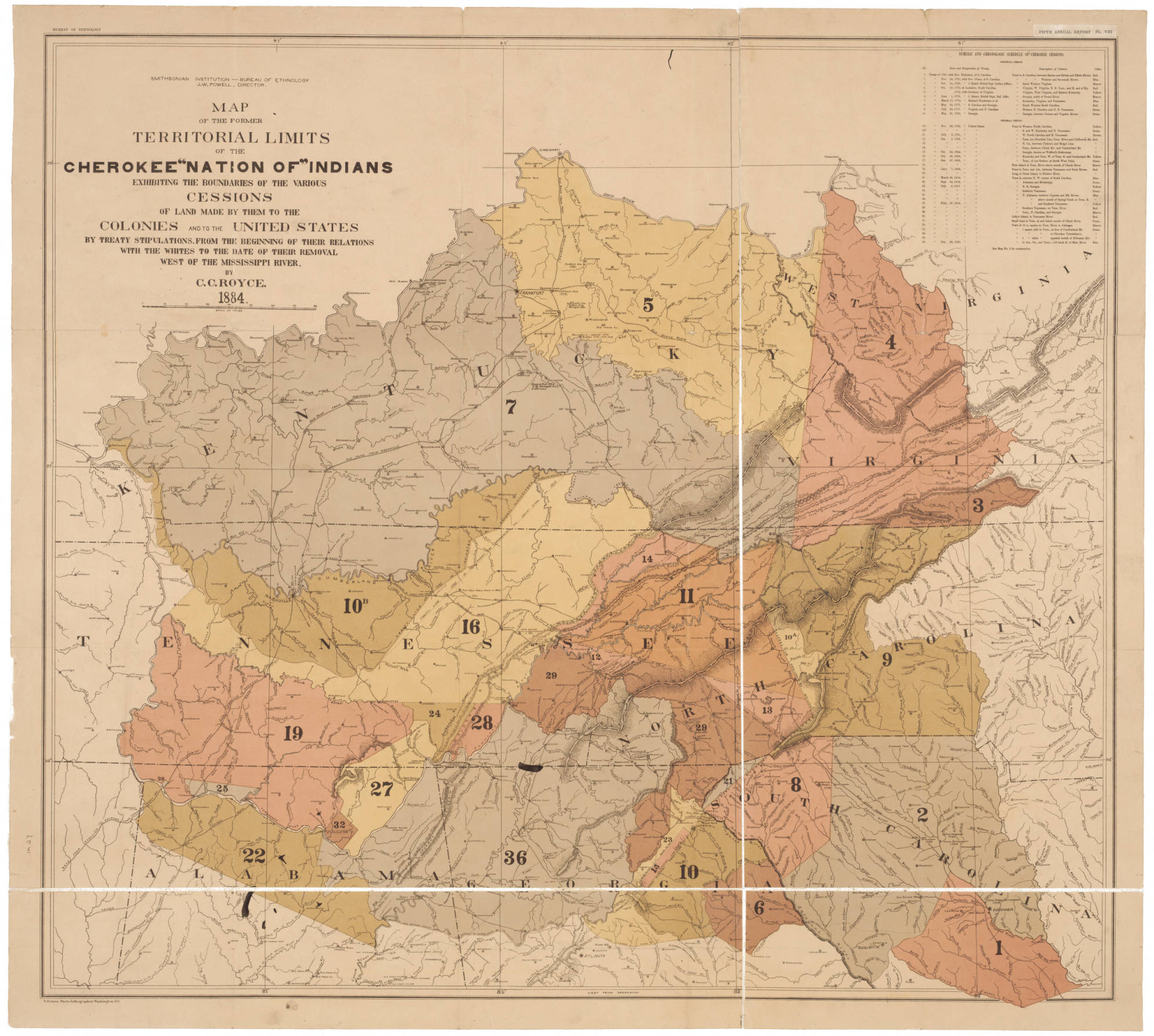

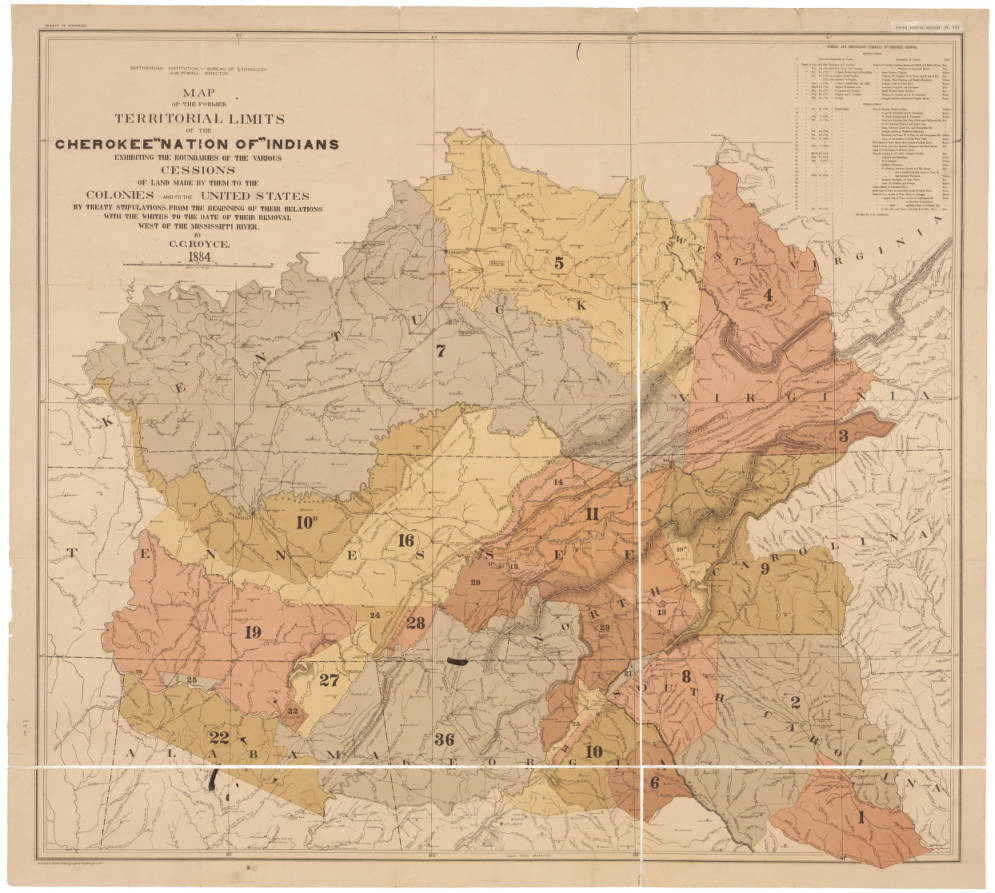

Leading up to the 1832 case, gold was discovered in northern Georgia on lands belonging to the Cherokee Nation. Starting in 1828, prospectors and miners rushed into Cherokee territory, predating the famous California Gold Rush in 1849 by over twenty years to become the first American gold rush. The Georgia State Assembly passed acts attempting to eliminate Cherokee rights to the land, and the state utilized a land lottery to systematically confiscate Cherokee lands to give them to white Georgians. Samuel Worcester and Elizur Butler, two white Americans peacefully living on Cherokee lands, often advised the Cherokee about their rights as a nation. To stop this, the Georgia legislature passed a law prohibiting whites from living on Cherokee lands without permission from the state. Worcester and Butler were arrested,

and their trial in Worcester v. Georgia challenged the arrest by questioning the constitutionality of the state imposing laws on a foreign nation. Marshall’s ruling in the case legitimized the Cherokee Nation’s sovereignty, meaning that a state, like Georgia, could not impose laws on a foreign nation. The federal government (a sovereign state) held the sole power to enter into treaties or other agreements with foreign, sovereign nations under the Constitution. President Jackson strongly disagreed with Marshall and expressed in a letter to a friend: “The decision of the Supreme Court has fell still born, and they find that it cannot coerce Georgia to yield to its mandate.”

Jackson’s message about the Supreme Court’s decision highlights a limit to the power of the judicial branch: it cannot enforce its rulings alone. Marshall’s ruling had no effect and could not protect the Cherokee Nation. The executive is the commander in chief of the military, who held the power to forcibly remove the Cherokee from their lands. In addition, Congress passed the Indian Removal Act that forced eastern American Indian tribes to move west of the Mississippi River, and Jackson signed it in 1830. The state of Georgia took possession of Cherokee lands in 1835. Significant portions of the Cherokee were forcibly removed in 1838. That journey westward became known as the “trail where they cried,” or the “Trail of Tears.”

Explore the resources below to learn more about the Judicial Branch and Indian Removal.

The Georgia Historical Society Archives houses these materials related to Cherokee Indian Removal:

- Cherokee Indians Relocation Papers, Georgia Historical Society, MS 0927

- John A. Cuthbert letter, 1834, Georgia Historical Society, MS 1721

- Andrew Jackson letter, Georgia Historical Society, MS 67-01-01-07

- Record of Spoliations (Claims), No. 1, 1836-1838, 1 volume. Kept by Wilson Lumpkin and John Kennedy, Commissioners appointed by President under Cherokee Treaty, 1835. 423 claims. Statement on last page is oath taken by Stand Watie, Interpreter to the Commissioners, December 3, 1836. Signed by Watie, Wilson Lumpkin, and John Kennedy. A postcard photo of Watie is laid in, Georgia Historical Society, MS 927-01-02-09

- Land Grant to Elisha Strickland of Meriwether County, Georgia, Georgia Historical Society, MS 769.

- Grant of Lot 525 in the 19th Dist. 3d Sec. Cherokee County (40 acres) to Dempsey McCoulars of Parr’s District, Burke County, Ga., Dec. 12, 1835, Georgia Historical Society, MS 517-01-01-01

- Item 1: Land grant from state of Georgia to John P. Riley. Signed by William Schley, Governor. Lot no. 1080, 12th District, 1st Section, Cherokee County, 40 acres. Plat with pendant seal included., Georgia Historical Society, MS 661-01-01-01.

Today in Georgia History: Worcester v. Georgia

Today in Georgia History: Georgia Supreme Court

Today in Georgia History: Dahlonega Gold Rush

Today in Georgia History: Cherokee Constitution

Primary Source Set: Westward Expansion in Georgia Between 1789 and 1840

Three Centuries in Georgia History: Nineteenth Century, Growth and Change in Georgia

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Worcester v. Georgia, 1832

New Georgia Encyclopedia: Cherokee Removal